Carbon dioxide dissolves in water to form carbonic acid which causes what is known as

sweet corrosion. The product of this form of corrosion is iron carbonate which forms as a film

on the metal surface. At higher temperatures (+80oC) this film has protective qualities leading

to lower than expected corrosion rates at higher temperatures. Sweet corrosion is typically

observed as metal wall thinning and shallow pitting. Under high velocity conditions deep

elongated pits are sometimes observed.

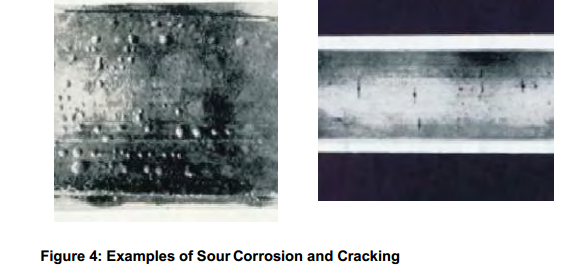

Hydrogen Sulphide dissolves in water to cause what is known as sour corrosion. The product

of this form of corrosion is iron sulphide. The low solubility of iron sulphide in water results in

the formation of a dark or black corrosion product film that is able to protect the steel surface

from general corrosion even in aggressive systems. However due to the conductive nature of

the protective film any local break in the iron sulphide layer can result in very severe pitting.

Hydrogen sulphide may also cause hydrogen damage in susceptible steels. The reaction

which gives rise to the iron sulphide film releases atomic hydrogen which can then diffuse

into the steel where it can lead to the formation of hydrogen blisters or through wall cracking

(Sulphide Stress Corrosion Cracking or Stress Oriented Hydrogen Induced Cracking).

Microbial Corrosion

Microbial corrosion is caused by the action of bacteria contaminated systems, commonly sulphate reducing bacteria (SRB’s). It is not the bacteria themselves that attack the metal but the local environments that they create and contribute to that leads to corrosion of the structure. Microbial corrosion is typically a problem inside pipes which are left with stagnant water, at dead legs and in the bottom of tanks. For microbial corrosion to occur conditions must be suitable to support bacterial life. These requirements include:

- Presence of bacterial life in the system.

- Source of Sulphate.

- Source of Carbon.

- Source of water.

- Anaerobic conditions.

- Close to Neutral pH.

- Suitable temperature and pressure for bacterial life to be sustained.

Atmospheric Corrosion

Moisture, oxygen and aggressive species such as sulphate, nitrates and chlorides present in

the atmosphere can lead to atmospheric corrosion occurring on exposed structures.

Atmospheric corrosion proceeds under the same mechanism as wet corrosion however as a

bulk liquid phase is only present during rainfall the corrosion reactions proceed in a thin film

of condensed or absorbed moisture on the metal surface.

The major factors that affect the rate of atmospheric corrosion at a given location are the

moisture levels and the concentrations of aggressive species in the environment. Marine

environments for example with high levels of chlorides present would exhibit significantly

greater corrosion rates than inland environments with low levels of chloride. Similarly

exposed metal structures in industrial locations with high levels of pollution and therefore

higher levels of sulphates and nitrates than rural locations would record higher atmospheric

corrosion rates than would be observed in rural locations.

Source:http://www.hse.gov.uk/offshore/ageing/ageing-plant-summary-guide.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment